Author’s note: I always give careful thought before publishing offensive ads in articles or including them in presentations, but unfortunately, I think it is often essential so that the reader or audience can fully appreciate the story. Nevertheless, I should like to apologise for any offence that is caused by the ads included in this piece.

Text:

This October has marked Black History Month, so as an advertising lawyer, I thought it would be interesting to delve into my personal archive of ads and try to ascertain whether there are any patterns in the ads that have caused racial offence over the last couple of decades. Is the occurrence of ads causing racial offence getting more prevalent? How does the UK compare with the rest of the world? And finally, who should be called out as the biggest culprit of all when it comes to publishing racist ads?

As someone who is pale, male and if not stale, then rapidly approaching my Best Before date, I should start by making an acknowledgement. I am not well placed to judge whether an ad is racially offensive, particularly to Black people, as I’m not Black. In thinking about the history of Black people in advertising, I have been struck, however, by the way in which British advertising has successfully incorporated members of other ethnic groups into advertising campaigns that have been effective in both their creative and commercial ambitions, but also beloved by the ethnic group being portrayed.

The paradigm example is the Beattie campaign featuring Maureen Lipman and created by Abbott Mead Vickers for British Telecom in the early 1980’s. I remember seeing the ad with the teenage boy sitting on the stairs, relaying his not very impressive O-level results to his grandmother, Beattie. She seizes on the fact that he has achieved a pass in sociology. “An ology” she declares. “You get an ology, you’re a scientist!” Across the entire series of ads, Jews laughed with the advertising because they recognised their own mothers and grandmothers. Gentiles laughed with us, not at us. My only concern at the time was that Maureen Lipman’s characterisation of Beatie was so uncannily reminiscent of my own grandmother that I began to wonder whether BT were tapping our phone, looking for inspiration.

It is difficult to think of an ad or a campaign that has pulled off the same trick with the Black community. There have been campaigns that have been led by Black actors, such as Sir Lenny Henry for Premier Inn, but he was very much being himself, rather than a character, with no reference to his ethnicity or the culture of the Caribbean. On re-watching an old TV ad from 1981 for “Lilt, with the totally tropical taste” I was shocked to realise that while the reggae inspired soundtrack remains as fresh as the pineapples and grapefruit used to make the drink, there is not a single Black person in the ad. Even the waiter handing the glasses of the cool, refreshing Lilt to the beautiful young Caucasian people appears to be white, although it’s hard to be sure as only his forearms are in shot. But the cultural appropriation is clear enough.

Perhaps the greatest success that has been achieved by British advertising reflects something that was mentioned by Baroness Floella Benjamin, DBE, when she appeared recently on Dessert Island Discs (16th October, 2020). Dame Floella recounted a story of when she was presenting Play School in 1976. She asked the producer whether the illustrations for their children’s stories could include not only white kids, but also Black, Asian and Chinese kids, “because I want the children out there to feel that they belong to that culture.” The change was made that day, and Dame Floella continues, “because if you don’t see yourself, how do you know you belong? How do you know you’re important?”

Reflecting on these comments, I think it is reasonable to say that in more recent years, the more frequent casting of Black people in advertising has hopefully helped to progress this sense of belonging, particularly when cast as the ‘heroes’ of a TV commercial, and not just as walk-on artists in the background. For example, my personal favourite of the long series of fantastic Christmas ads created by adam&eveDDB for John Lewis is “Buster the Boxer” from 2016, with the CGI animals bouncing on the trampoline in the garden on Christmas morning. The family that feature in the ad happen to be Black, but they could be of any ethnicity. Hopefully, this casting is a good example of what Dame Floella describes as signalling that Black people belong to British Council. Sadly, and worryingly, things appear to have gone backwards since 2016.

Where were we at the start of the millennium?

It is difficult to find many reports of ASA investigations into the depiction of race in advertising until 1998 and therefore dangerous to make assumptions about the reasons for this absence. Of course, a higher proportion of advertising was on television or radio, and therefore subject to mandatory pre-vetting. Most non-broadcast advertising was either in newspapers or Out-of-Home, and even without pre-vetting, the media owners were well aware of their compliance obligations under the Advertising Codes. For many years, the British Codes of Advertising have prohibited ads that contain anything that is likely to cause serious or widespread offence, particularly in relation to certain specific characteristics, including race. The focus of the ICC Code is slightly different, however, prohibiting ads that incite or condone any form of discrimination, including that based on ethnicity.

The Commission for Racial Equality has been at the vanguard of confronting the issue of racism through advertising for decades. Some of their excellent, hard hitting work can still be seen on the website of the History of Advertising Trust. The CRE’s TV and cinema ad from 1996, “Them” is still very powerful, and ‘remainers’ might be forgiven for wishing it had been broadcast again before the EU Referendum in 2016.

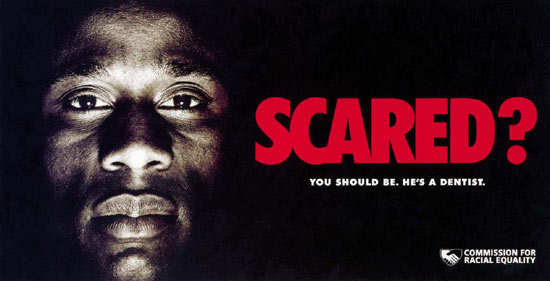

Unfortunately, however, one of the first published ASA adjudications on the issue of race comes around this time, in 1999.

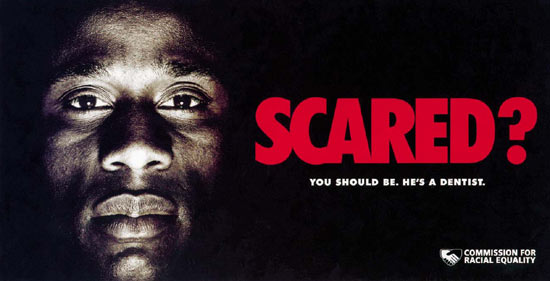

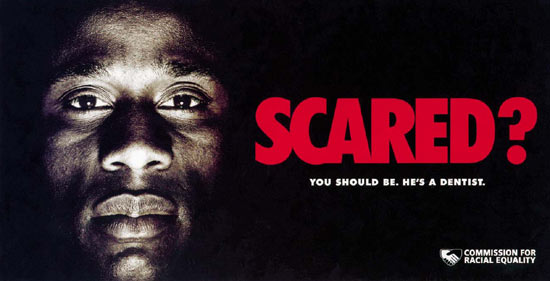

This was a poster ad that was part of a campaign by the CRE to make people confront their own attitudes to racial stereotypes. The original teaser just had the same image and the headline, “Scared?” The reveal then had the sub-heading, “You should be. He’s a dentist” and identified the advertiser as the CRE. The campaign provoked one of the largest number of complaints ever in this area, 84, with people not only complaining about the racism of the teaser, but also the denigration of dentists and the danger of discouraging children from visiting the dentist. The CRE argued that the ad was an ironic and humorous challenge to stereotypes. There appears to have been no formal adjudication by the ASA, and it is difficult to get to the bottom of what happened in this case, but the upshot was that the CRE became the first advertiser (along with TalkRadio, by way of contrast), to be required to have their posters pre-vetted for 2 years by CAP Copy Advice – a procedure that had really been introduced to deal with the notorious FCUK campaign of the time. However, it seems that the ASA and CAP were uncomfortable with the use of shock tactics, which is a long-running bugbear, and perhaps about the lack of prior consultation.

Have commercial advertisers tried to challenge racism?

Yes, but with varying degrees of success.

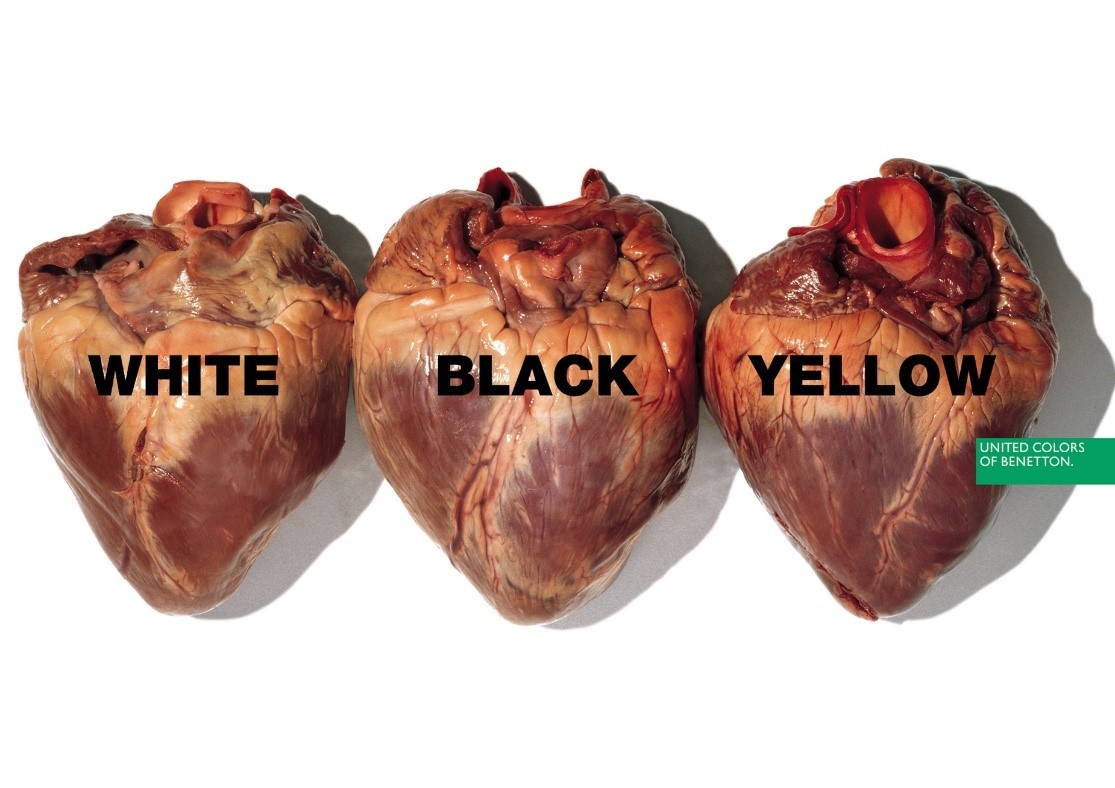

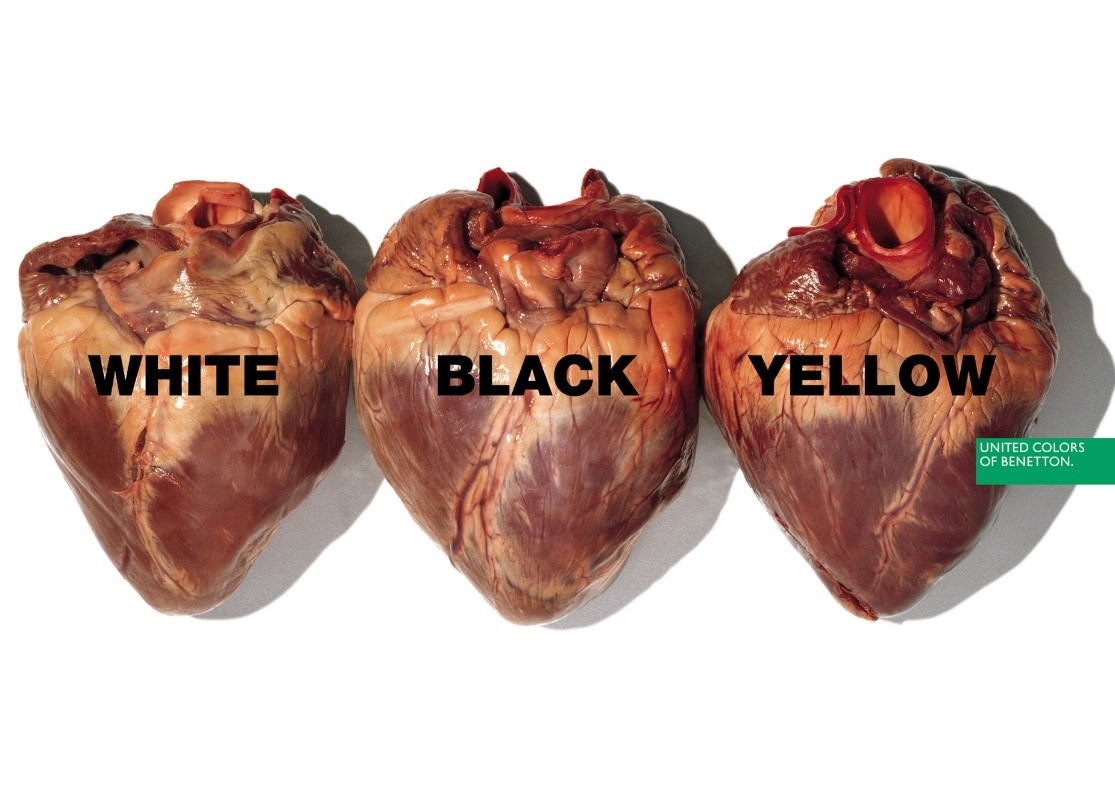

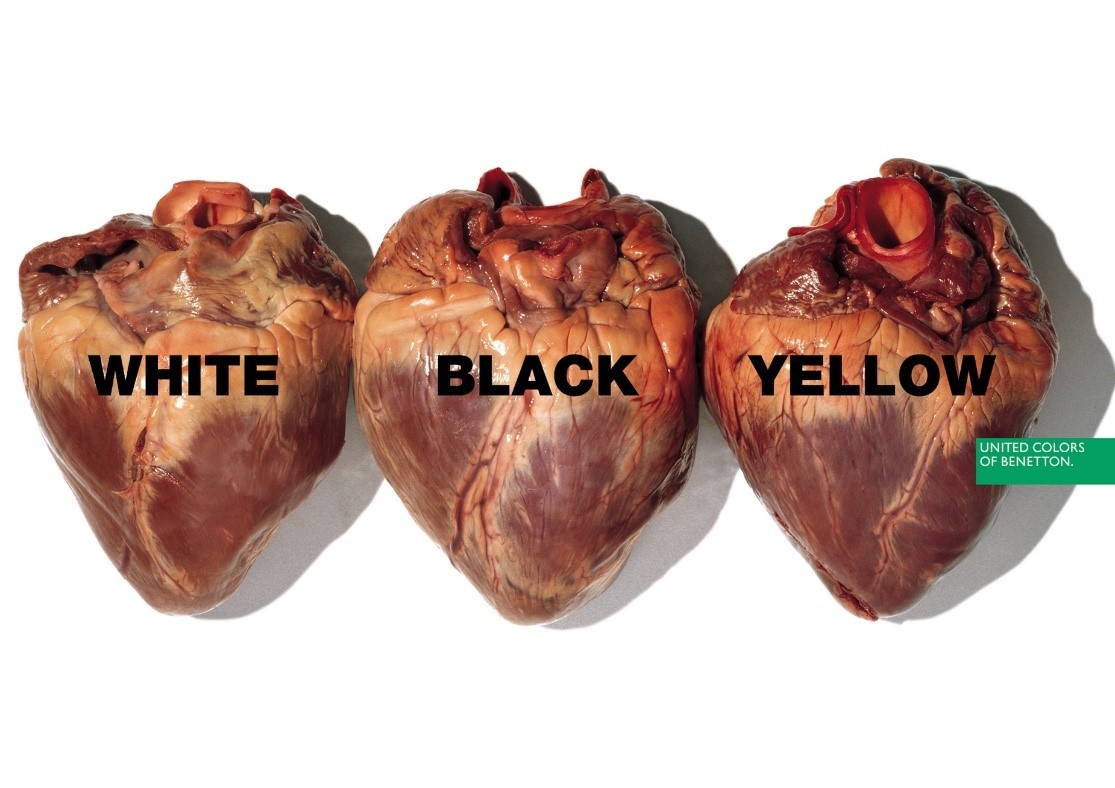

By far the most successful advertiser in this vein has been Benetton. This simple Benetton ad from 1996 must be one of the most memorable anti-racism ads of all time.

Unfortunately, however, even Benetton came unstuck from time-to-time, and I understand that the ad below of the three kids of different ethnicities caused considerable offence in Saudi Arabia, where it is considered offensive to display an internal organ. In this case, being the tongue.

More recently, other advertisers appear to have made genuine efforts to challenge stereotypes. Even assuming they were working in good faith, and there is no reason to think otherwise, they have ultimately come unstuck.

In 2016, Nicofresh published this poster ad for an e-cigarette product on various Out-of-Home sites, but only in Belfast. So while there were only 6 complaints, it is worth considering that in the context of a media schedule with a limited geography. Of these complaints, 6 people complained that the ad was racist, implying that an interracial relationship was taboo, and 4 of these 6 also thought that it was offensive to imply than an inter-generational relationship was taboo. Nicofresh’s defence was essentially, ‘yes, that’s the point’. Our product means that smoking will no longer be taboo, just like these relationships are no longer taboo. The ASA seem to have been very hard on Nicofresh in this case, as well as on the ‘Average Consumer’, who apparently would have missed what seems to be a fairly clear message. There is also no reason to think that Nicofresh were blowing a dog-whistle. What would they possibly have to gain?

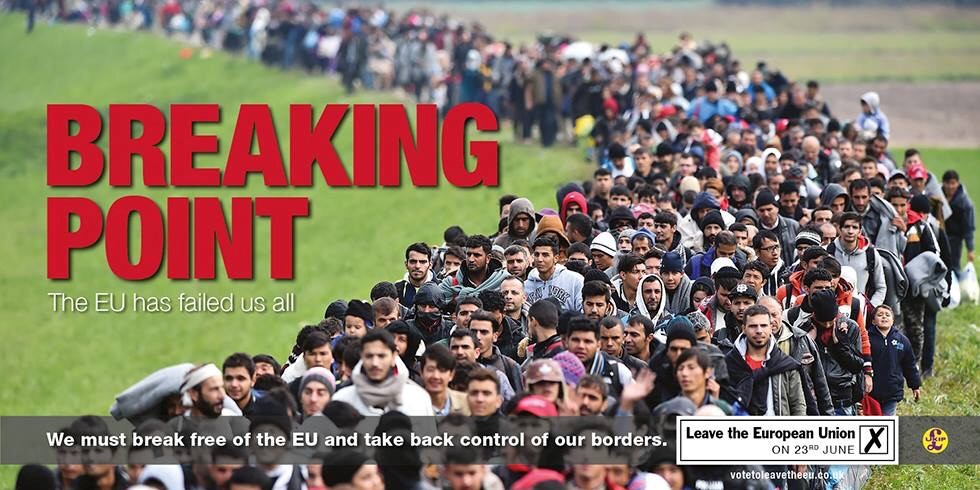

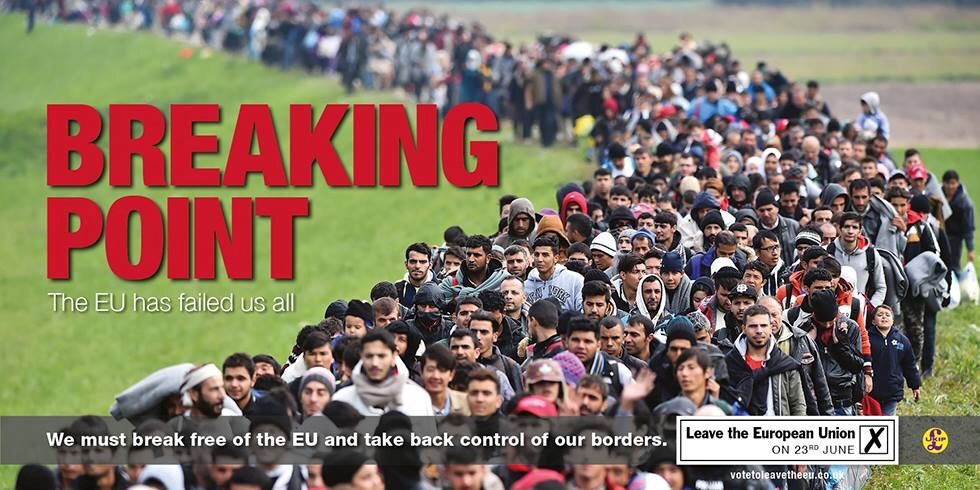

And on the subject of dog-whistles, the sad fact is that some of the most egregious and deliberately racist ads of the last 20 years, if not of all time, have not merely escaped censure by the ASA, but have managed to avoid the application of the Advertising Codes altogether, because they have been ‘political ads’ published in the course of an election campaign. Or in this case, a referendum. That referendum.

Have any advertisers been more ambitious in using Black and Caribbean culture?

Yes, but unfortunately attempts to go beyond simple casting on a ‘neutral’ basis in ads have back-fired badly, as illustrated by the Cadbury’s campaign for Trident Gum in 2007.

The expensively produced TV and cinema ad, with high production values, featured a West Indian dub poet waxing lyrical about the virtues of the new Trident gum, and finishes with him on a yellow tourist amphibious ‘duck boat’ passing the Houses of Parliament, shouting “mastication for the nation.” It seems inconceivable that with their advertiser, or their agency, JWT, has any intention of being racist. Cadbury had not only sought the views of the Afro-Caribbean community and the general public during the campaign’s creative development, but being a TV ad, they had also obtained pre-clearance from the Broadcast Advertising Clearance Centre, now Clearcast. Although Cadbury admitted that a few people had found the ad offensive during their consumer testing, that cannot have prepared them for the tidal wave of 519 complaints, propelling the ad into second place in the list of the most complained about ads of 2007. Although the ASA appeared to accept that Cadbury and JWT had acted in good faith, they found that “The stereotype depicted in the ads had, unintentionally, caused deep offence to a significant minority of viewers and that many of those who complained to us were concerned that the negative stereotype could be perpetuated.”

Unfortunately, it is hard to avoid the conclusion that this case may have had a chilling effect on any more ambitious attempts to give Black and Caribbean culture a more prominent role in British advertising.

Overall, is the issue of racism in advertising getting better or worse?

Sadly, it is difficult to avoid the conclusion that that situation has become worse in the last few years.

Some examples just leave you wondering what were they thinking of? Or even, were they thinking at all? Or was there no adult in the room when they decided to publish the ad. This is particularly true of ads published on companies’ own websites, which do not go through any process of pre-vetting. In several cases, the court of public opinion, as exercised through social media, has adjudicated so quickly that the ads have been withdrawn before the ASA have had an opportunity to investigate.

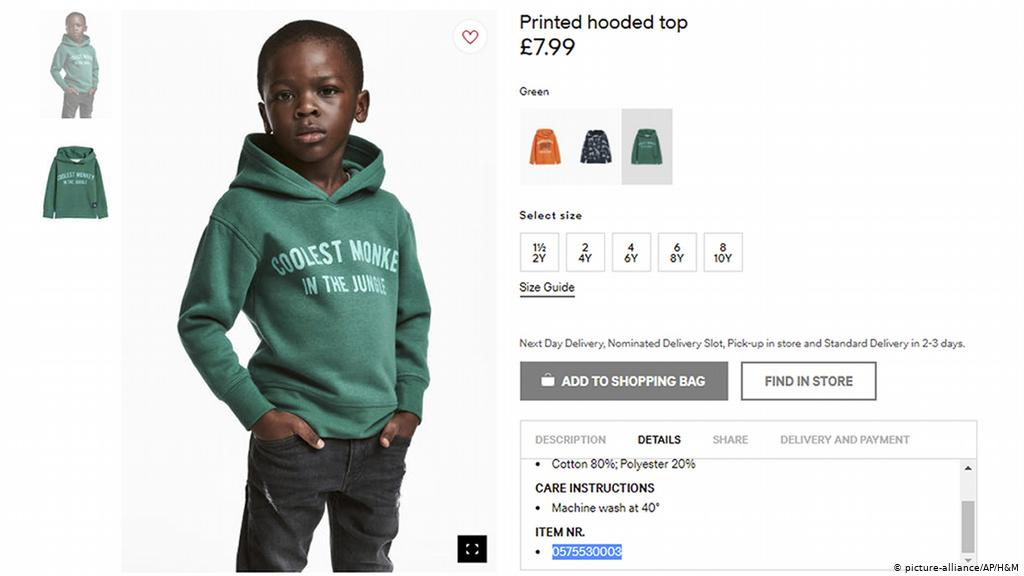

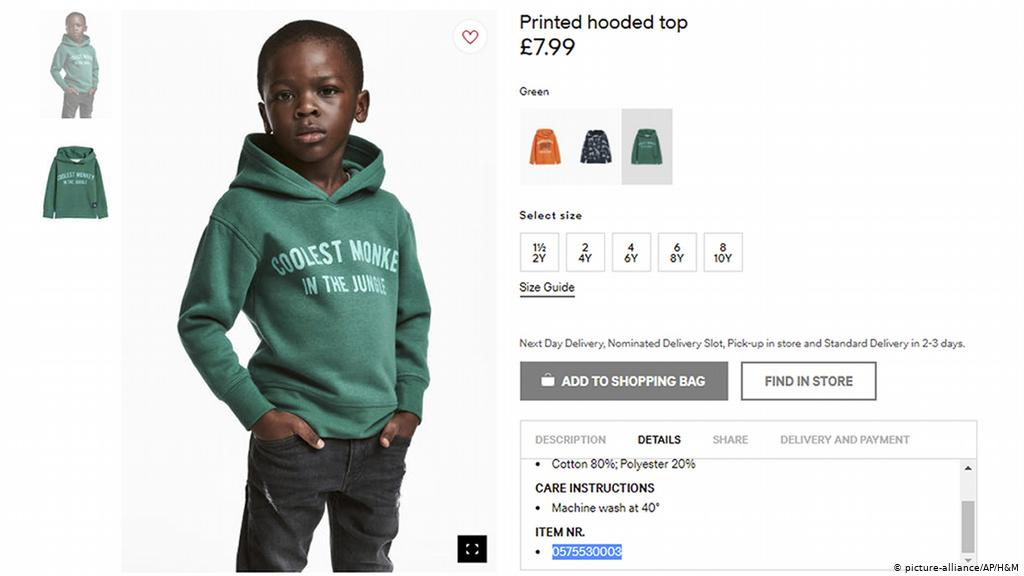

This notorious ad by H&M featuring a Black boy wearing a hoodie with the legend “Coolest Monkey in the Jungle” was quickly withdrawn by H&M when it was pointed out to them on social media, quickly and in no uncertain terms, that the ad was wildly inappropriate.

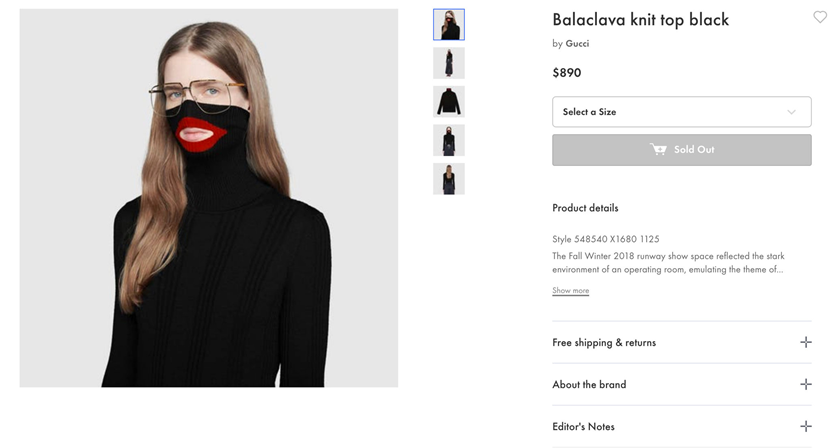

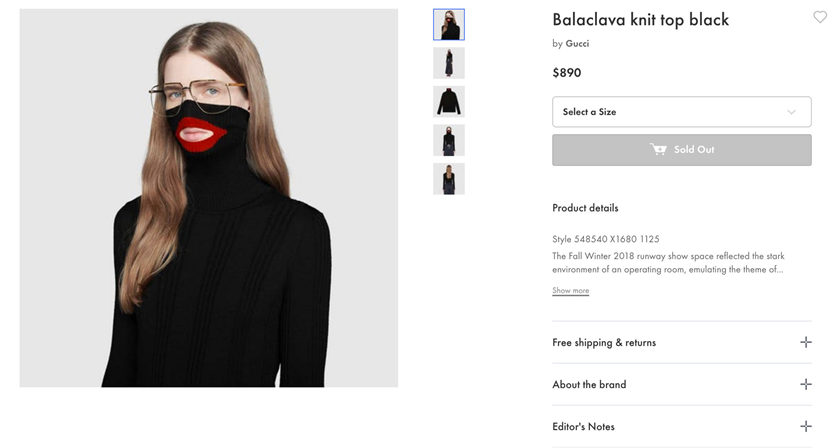

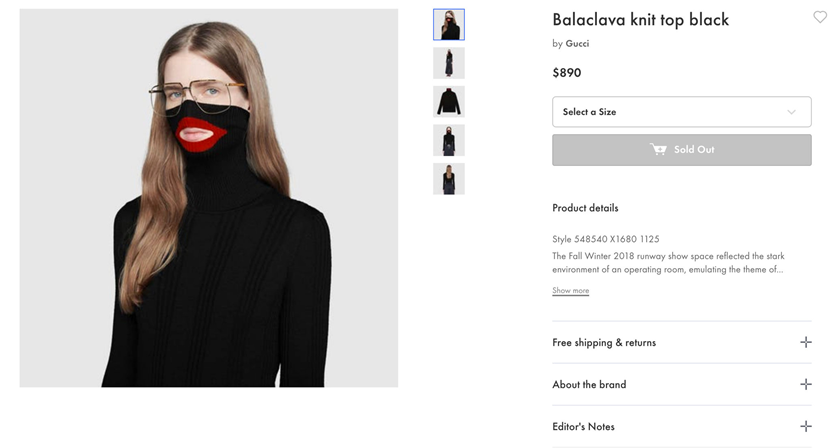

While some commentators were prepared to give H&M the benefit of the doubt, accepting that young creatives are ‘colour blind’ and failed to spot the issue in advance, this ad for Gucci is just incredible.

It is quite incredible that in 2019, a major corporation could publish that advert and fail to spot the allusions to ‘black face’ which had only recently been the subject of considerable controversy, following the publication of some old photos of Justin Trudeau, the Canadian Prime Minister, who had worn ‘Black face’ on a number of occasions in his past. The creative director denied that the ad was intended to be racist.

Unfortunately, however, it is pretty difficult to deny the racist intent behind a couple of ads that the ASA have investigated in recent years, and particularly since 2016.

This regional press ad, with very limited circulation in the Purbeck Gazette in June 2016 (what else was happening in June 2016?), was for The Ginger Pop Shop, and not only featured a ‘golly’, but also the headline “English Freedom”. Despite the tiny media, 2 people complained to the ASA that the depiction was racist and offensive. The advertiser’s defence, as dutifully recounted by the ASA, is at best unconvincing, and at worst, insincere. The ASA also noted that “the inclusion of the words “ENGLISH FREEDOM” in the ad was likely to contribute to that offence, because in combination with the image it could be read as a negative reference to immigration or race. We therefore concluded that the ad was likely to cause serious or widespread offence.” This is a reminder that even a small number of complaints, such as one or two, can give rise to an upheld complaint, and that offence can be serious, even if confined to both the readers of the Purbeck Gazette.

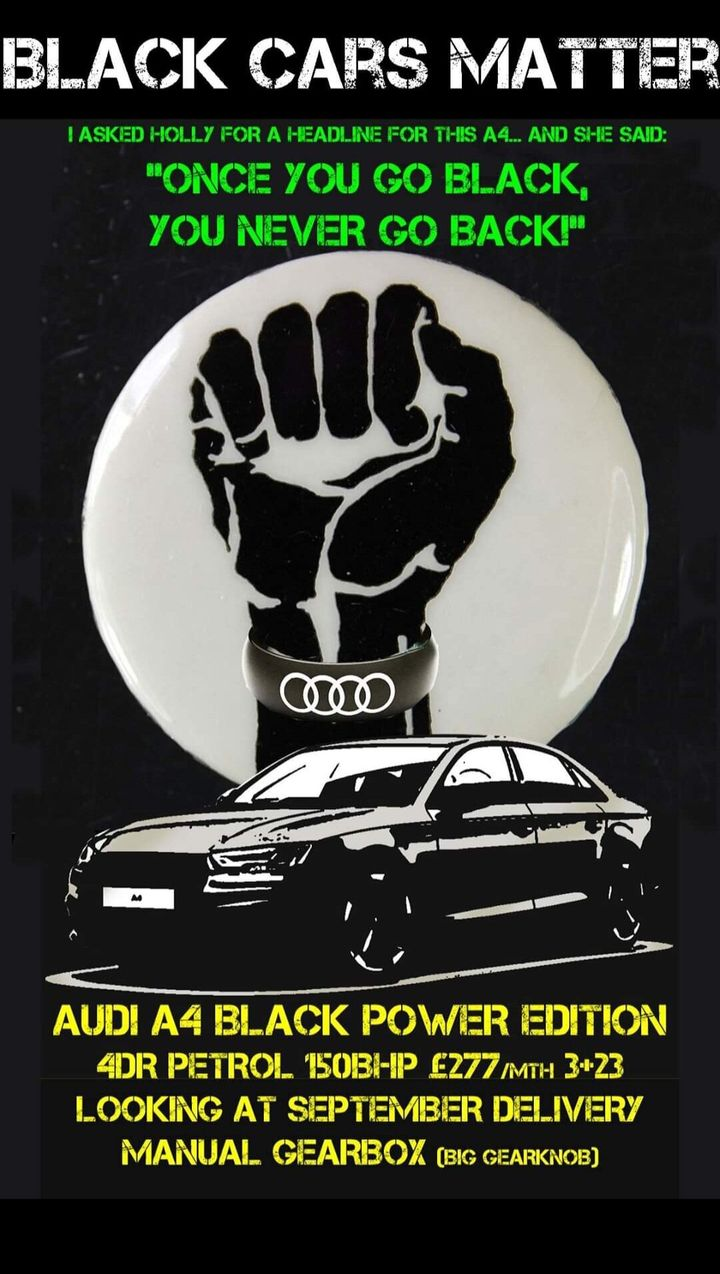

The murder of George Floyd and the rise of Black Lives Matter has also provoked what might be a cynical backlash or might be a cynical attempt to ride on the back of movement. Neither explanation is particularly attractive. The final example in this section brings us right to date, with the ASA adjudication being published on 23rd September 2020, just over 5 weeks ago.

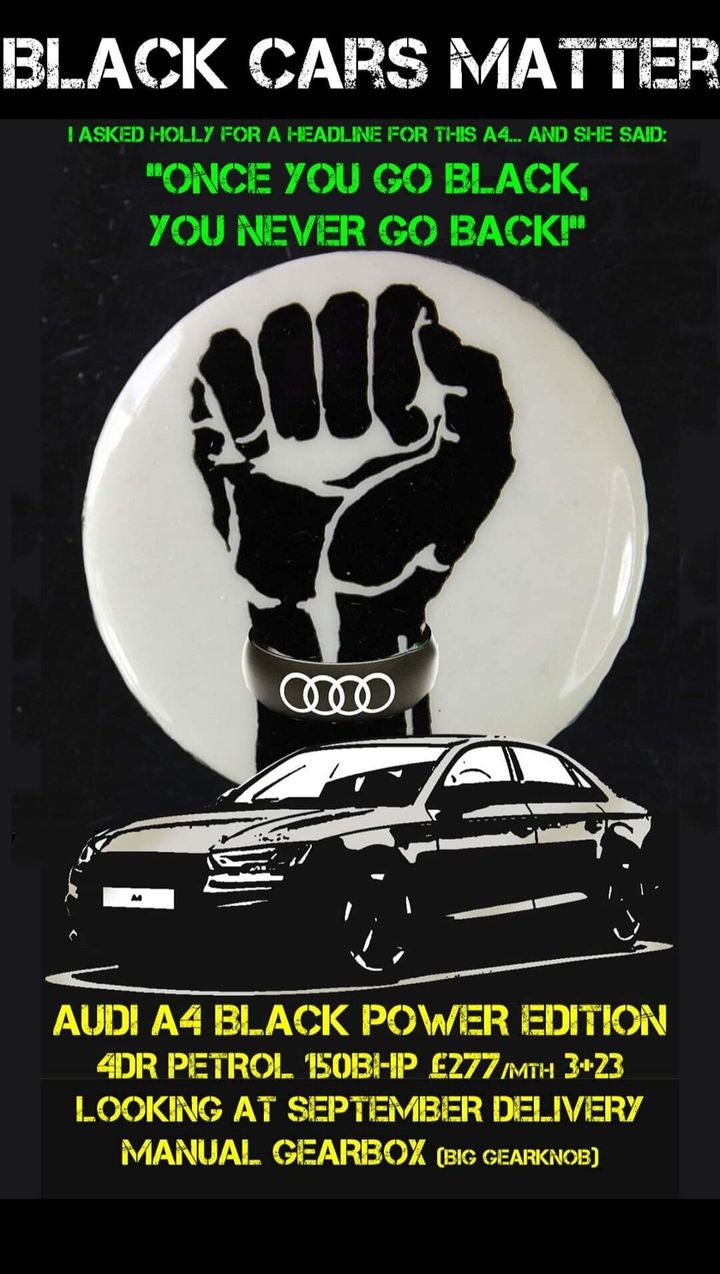

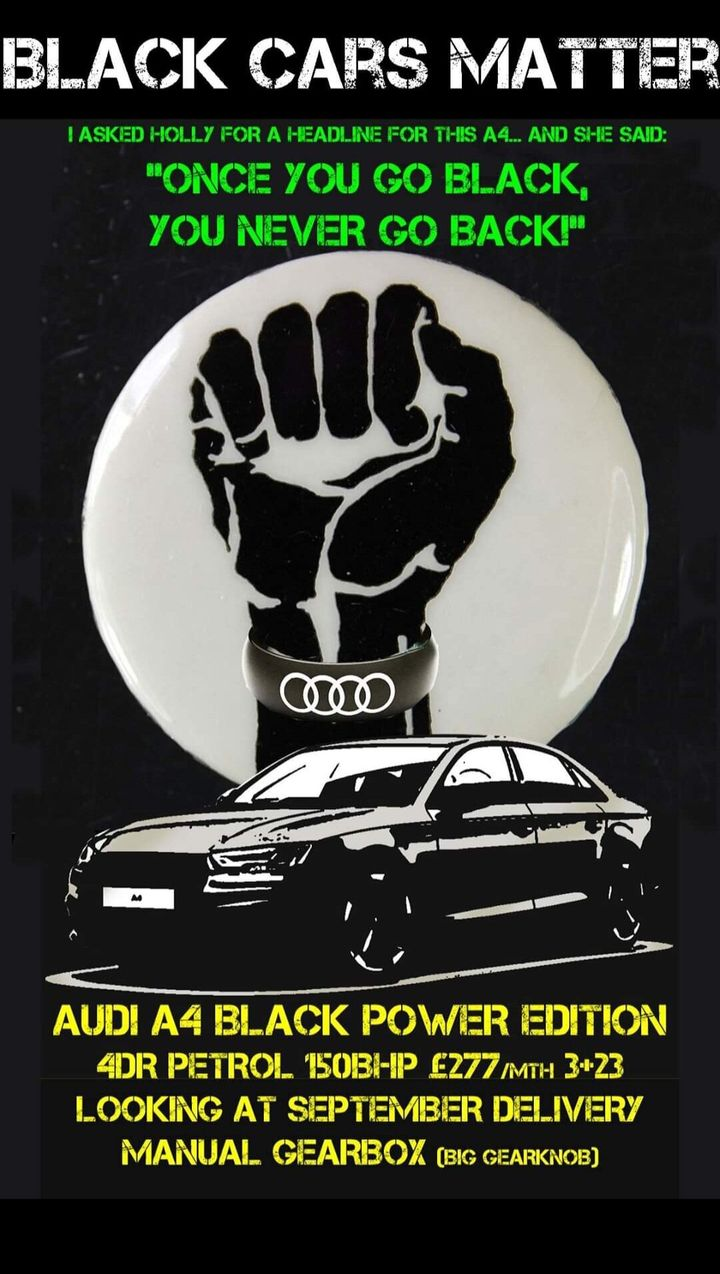

A car leasing company, LINGsCars, posted a Facebook ad in June 2020. The ad included the image “BLACK CARS MATTER. I ASKED HOLLY FOR A HEADLINE FOR THIS A4…AND SHE SAID: ‘ONCE YOU GO BLACK, YOU NEVER GO BACK!’”, with an image of a black raised hand fist with a wristband displaying the Audi logo and a black Audi car. (For the avoidance of doubt, the ad had nothing to do with Audi or its advertising agency.) Once again, the ASA rejected the advertisers wholly unpersuasive explanation, and concluded that using the slogan and iconography to draw attention to an ad for a car trivialised the serious issues raised by Black Lives Matter. In addition, the line, ‘Once you go black, you never go back’ objectified and fetishized black men.

So how do we compare with the rest of the world?

My personal consumption of advertising outside the United Kingdom is pretty limited, and mainly confined to watching lengthy advertising breaks on CNN in hotel rooms in the United States, while waiting for brief snippets of news. My not very scientific and anecdotal evidence is that Black people are seen more often in British advertising than in US advertising, and that while you may see Black couples on TV ads in the States, you are more likely to see a mixed race couple in a British ad. However, I have no data to back up this perception, and I would be happy to be proved wrong.

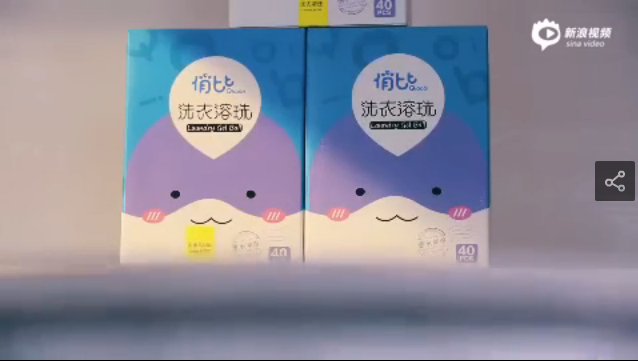

But probably the most breath-takingly racist ad that I have ever seen is a TV Commercial from China.

The story board above explains the ad. We start with an attractive young Chinese woman who, for reasons that were never explained, is visited in her apartment by a young Black man, whose voice betrays his roots as a likely lad from the East End. I’d guess Poplar, but possibly Bethnal Green. Although attracted to the young man, she is clearly perturbed by his ethnicity, so she somehow manages to put him into her top-loading washing machine, inserts the soap powder being advertised, and hey presto, he comes out Chinese. Her dilemma is resolved. You have to watch it to appreciate the fully awfulness of it.

So finally, what is the most racially offensive British ad of all time, and who was the advertiser?

This is more than just a numbers game. If it was, the winner would be the Trident ad, based on the number of complaints to the ASA, at 519.

However, in Cadbury’s defence, even the ASA accepted that they had not intended to cause racial offence, and the racism was inadvertent.

Also, there are some political parties, such as UKIP, of whom expectations are low in this regard. There are other examples mentioned above of marginal advertisers being deliberately provocative or mainstream advertisers being inattentive.

The ad, however, by the Home Office, comes from the UK Government, of whom it is reasonable to expect better. And the intention was clear: this was part of Theresa May’s attempt to create a hostile environment, which ultimately led to the shameful Windrush scandal, and brings us back full circle to families of Black Britons, such as Baroness Floella Benjamin, whose family came here – perfectly legally – from Trinidad in the 1950’s.

The ASA’s adjudication into the 224 complaints is long and complicated, dealing with 5 issues, 2 of which concern offensiveness, being the use of the phrase ‘Go Home’, the potential to incite racial hatred, and 3 of which concern the factual accuracy of various claims made in the ad.

The adjudication was published on 9th October 2013, well before the full horror of the Windrush scandal had unfolded. The surprising thing now, however, in the light of the that scandal, which resulted in the subsequent Home Secretary, Amber Rudd, being metaphorically thrown under the bus, is that while the ASA upheld 2 of the 3 complaints about factual accuracy, the 2 complaints about causing racial offence were rejected. The ASA accepted that the use of ‘Go Home’ was contextualised by the reference to illegal immigrants. Of course, at the time, the ASA was not to know that many of the people who were subsequently threatened with deportation would end up proving that they are here perfectly legally. The ASA also accepted that the reference to people facing deportation was targeted at illegal immigrants, not legal ones. To be fair to the ASA, its not their fault that the Home Office couldn’t tell the difference.

So where are we now?

It is clear that there is still a major problem with racism in advertising. Although many mainstream advertisers are helping to create an inclusive culture where young Black Britons will be encouraged to feel that they are part of the culture and they belong here, attempts to really celebrate Black and Caribbean culture in our advertising have so far not succeed. Meanwhile other advertisers seek to exploit or create division, and others just lazy or inattentive to the offence that they cause, which is arguably even worse.

So, while we’ve come along way from the days when the ‘golly’ was used to advertise marmalade, or Lilt ads were shot in the Caribbean without a single Black person, it is clear that we still have a very long way to go.

Related Item(s): Advertising & Marketing, Brands and IP newsnotes – issue 5, Retail, Hospitality & Leisure

Author(s)/Speaker(s): Brinsley Dresden,